Our tribute to Francesco Nuti

The memory of the great Florentine actor and director through his most iconic films and the words of journalist Piero Ceccatelli

Francesco Nuti was a perfectly legitimate son of Prato. In the formation of character, in the merits and also in certain excesses and defects. Certainly, Prato immediately recognised his talent (a fact not taken for granted, for other fellow citizens) and loved him 'for better or worse'. Or, if not exactly loved, tolerated and forgave him, as character and events changed.

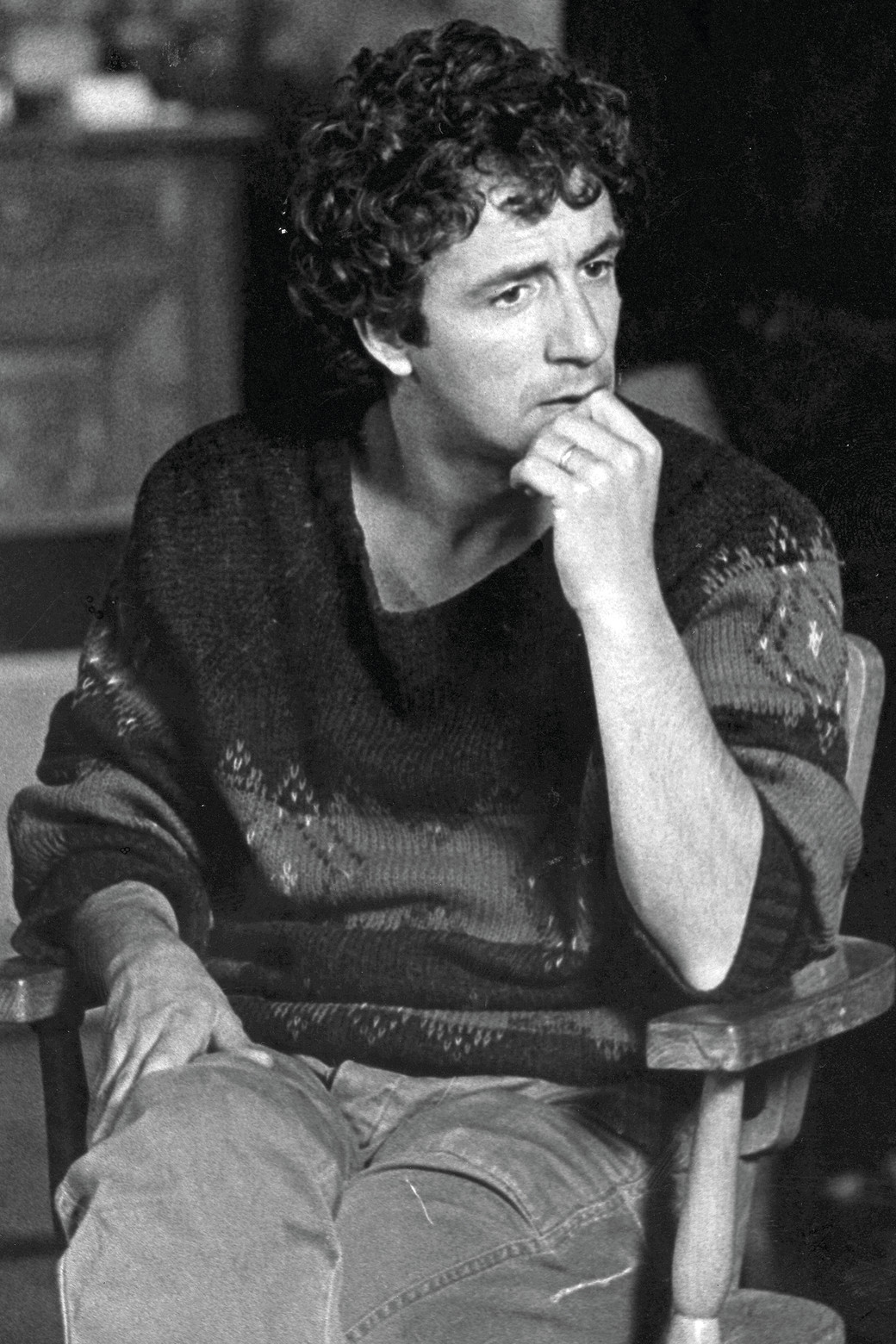

Francesco Nuti

Francesco NutiBorn in Florence, Francesco grew up in Narnali in his father Renzo's barber shop. Before his eyes, a comings and goings of male types, a melting pot of tales, outbursts, confidences, tall tales. He, shy by nature, observes and stores. Narnali is a collection of fields and factories around the road going to and from Pistoia. The factory that employs half the village is a wool mill named after Temistocle and Omero Nesi. Their grandson, Edoardo Nesi will win the 2011 Strega Prize with a book on the textile decline of Prato. With each passing day, Narnali is closer to the city, which stretches its tentacles with houses and warehouses. On the opposite side, Montemurlo grows without rules and advances until it touches Narnali. When Nuti arrives, Narnali was a village; by the time he is a teenager, it is already suburbia. Urban evolution (evolution?) allowed Francesco to become a Pratese without feeling like a country boy. After his death, a prophetic photo spread: Francesco Nuti and Paolo Rossi, more teenager than child, side by side in football shirts. Vulgate has it that Nuti was hatching a determination to succeed from an early age and dreamed of achieving it with football. He was good. But the comparison with Paolino would advise him to change field. After his death, a prophetic photo spread: Francesco Nuti and Paolo Rossi, more teenager than child, side by side in football shirts. Vulgate has it that Nuti was hatching a determination to succeed from an early age and dreamed of achieving it with football. He was good. But the comparison with Paolino would advise him to change field. By a twist of fate, Francesco took the right path by enrolling at the Buzzi, a school for textile and chemical experts, a training centre for work and 'practicality'. The Buzzi is also the school of the Pagliette, a goliardic group that smilingly flaunts the hats worn by grandparents and great-grandparents. The Pagliette are light-hearted and irreverent on freshers' day and their raids on rival schools, but very serious in staging the Rivista, a hybrid of cabaret and avant-garde show with texts inspired by Prato, which fills the theatre for weeks every spring.

Francesco Nuti

Francesco NutiActors, strictly current students and memorable exes. Those who do not act, are trovarobe, are looking for money, are masqueraders at the end all on stage, to the applause that unites obscure figures and protagonists. Among these, by popular acclaim, is Francesco Nuti. A student and Paglietta acts (his Pharaoh Tutankhamen is memorable) by 'right' and not by manifest bravura. For generations, the people of Prato have discovered at the Buzzi their talent for designing and dyeing fabrics and yarns, becoming tanners and industrialists. Francesco Nuti discovered there that his path was show business. There was no need for this, but it is a fine confirmation for a talent that was in the meantime contended by everyone in the city: the amateur companies that sprung up around Rodolfo Betti, à la Guido Monaco; like the show groups of which his brother Giovanni, a doctor and musician, was the leader; like the discotheques where he performed in the middle of the night. A Francesco Nuti in the mood for nostalgia recalls with extreme precision that on 14 April 1973, not yet eighteen years old, he went on stage at the 'Monaco' for Staccia Buratta l'Italia l'è un po' matta, proudly adding that from that day on, 'I have always brought home the boiled meat and, as an actor, I have never been hungry'. And in fact Nuti was called in the circles and in the houses of the people, in the small theatres that survived in every village and hamlet where he brought his debut work, Pollo d'allevamento: vita più meno standard di un uomo qualunque, a nome Chiaramonti. A success, legitimised by the creative coincidence that saw Giorgio Gaber, in the following months, on tour with the almost homonymous Polli d'allevamento. In the meantime, Nuti was appointed artistic director of Radio Prato. Like a small RAI, this followed the political set-up of the city, minorities included: that appointment was almost a public investiture. The radio turned out to be a small cage for Francesco, a thoroughbred horse not inclined by nature to orderly tasks and somewhat frustrated at expressing himself only with his voice. A closed-mouthed face like his, which already leads to distant comparisons with Chaplin, cannot remain hidden behind a transistor. A tight-lipped face like his, which already leads to distant comparisons with Chaplin, cannot remain hidden behind a transistor. In fact, Alessandro Benvenuti and Athina Cenci, the two third survivors of the eternally tormented group of Giancattivi call Nuti to complete the trio, already famous thanks to TV and raging in the theatres with a cultured cabaret prone to non-sense. Francesco brings the group back down to earth. Earth, as the concreteness of references. Earth, in the sense of Tuscany and its unmistakable dialect. The Giancattivi reciprocate by restoring Nuti's face and offering it to the forty-four million eyes of the Italians who, on the RAI at the end of the monopoly, follow Non Stop, which hosts the Giancattivi, now with Nuti on the team.

Francesco Nuti

Francesco NutiIt is 1978. Prato, which works tirelessly and enriches anyone who arrives there with good intentions, witnesses almost without realising it the exploits of young people who have sprung up spontaneously, like wild flowers (or Prato flowers...) and are on their way to immediate, dazzling careers. In fashion, Enrico Coveri, the most functional to the city and its rampant textile industry, is the youngest designer called from Paris to show the women's collections. Paolo Rossi, top scorer in Serie A with Lanerossi Vicenza scored three goals at the World Cup in Argentina. But it is in the show that the greatest concentration is found. Roberto Benigni from Vergaio, three kilometres from Narnali, has just filmed Berlinguer, ti voglio bene, directed by Giuseppe Bertolucci and, somewhat marginalised in Prato, settles in Rome, where his talent is understood and he takes off. Rome was already home to 21-year-old Pamela Villoresi, who left Prato as a young girl to express herself fully as an actress with a classical and dramatic register, the dawn of a career that would lead her to managerial roles in the theatre and to Sorrentino's call for The Great Beauty, which won an Oscar. Francesco Nuti is the only one to be immediately understood - and retained - by his city, which offers him inspiration and to which he gives back entertainment and a certain fame. In the melting pot of talent springing up in the Prato of the late 1970s, a 20-year-old emerges who ten years later will prove to be one of Italy's greatest writers. He is Sandro Veronesi, he hosts radio programmes and studies architecture. He writes for pleasure and to cut his teeth on a publication that comes out in January 1979. Entitled Il Mensile (The Monthly), it is published by a South Tyrolean publisher, Pino Hoffer, mixing investigations, satire, unpublished focuses on the city. And interviews. In issue zero, Sandro Veronesi, born in 1959, interviews Francesco Nuti, born in 1955. Friends on and off the radio. Sandro undresses Francesco with spicy questions.

Frame dal film Madonna che silenzio c'è stasera

Frame dal film Madonna che silenzio c'è staseraFirst of all with regard to the shadow that Roberto Benigni casts over him: 'Since Benigni broke out on a national level, I have suffered a lot,' Nuti admits, 'but if there is a similarity between him and me it is only because, both from Prato, we have had the same experiences, he in Vergaio, I in Narnali. I too have known the houses of the people. The bar scene in Pollo d'allevamento Ciao Chiaramonti is similar to Benigni's bar scene, but I didn't copy it from him, because I experienced it too'. "When people tell me I look like Benigni, it annoys me if they mean that I imitated him, which is not true as people know, and you too, who knew me even before Benigni was successful. If Nuti as he is was from Milan, there wouldn't be this problem'.

Live meat, in short. Veronesi turns to Prato's 'institutional' culture, to Ronconi and the Theatre Design Laboratory now at the centre of the rift between the PCI (which wants to continue) and the Psi (which wants to cut back).

Nuti responds as a free spirit. 'There is only this Laboratory, but none of the intermediate stages to fully understand it. I did not understand Ronconi's shows because I am not able to understand an experimental language right away. In order to avoid it being an elite show, interventions at the most popular levels are needed. We must bring theatre to the masses as a fact of culture, entertainment, and common participation'. A manifesto of theatre and entertainment signed by Nuti. That of immediate comprehension, which he brings to the stage from suburb to suburb alternating with appearances by twenty million viewers on RAI, together with the Giancattivi.

Frame da Tutta colpa del Paradiso

Frame da Tutta colpa del Paradiso After TV, the Giancattivi bring Francesco to the cinema. The power of Nuti lies in the fact that with his pilgrimage as a travelling actor in the suburbs he has imposed on the popular imagination the name of Donald Duck, a very real but potentially imaginary town on the outskirts of Prato with that improbable name. When in the film to Francesco's question "Where are you going?" Alessandro Benvenuti replies: "West of Donald Duck". Then, staring him in the eyes: "Un c'è Paperino? Here, west", a place is drawn that says everything and nothing, a coveted and indecipherable destination, a tiny transposition into space of the power that Waiting for Godot represents for the temporal dimension. Nuti's Prato imprint on the Giancattivi is such that the film bears a title linked to Prato. Without being irreverent, America was discovered by Columbus, but Vespucci gave it its name. Prato, Prato. The cordon is not severed even when the Florence of the 1980s, for once marvellous also for its liveliness in contemporary arts, envelops and embraces it.

Nuti, as every Prato native fatally does in partnership with someone, leaves and sets out on his own. And it is Prato and his own autobiography that inspires his film debut. Madonna che silenzio c'è stasera tells the story of a young man looking for work in a textile company (and he, employed at the age of twenty in a wool mill, had just left, definitively resisting the last temptation not to be an actor). Suggestions of Chaplin, with the loom rebelling against the man and the looms whose infernal noise prevents any dialogue. And those who work shout as loud as they can to be heard by their neighbours, who respond with gestures, revealing hands reduced to stumps, the definitive fresco of the city sick with eardrum injuries and work accidents. For Nuti, it is the consecration: from now on, it will no longer be possible to remain physically tied to Prato, Life will take place in Rome, capital of cinema and of a bit of everything in culture, the films will be shot in Florence and where he calls the industry of which Francesco is a formidable cog. He will return to Prato discreetly or conspicuously, with a custom-built car and girlfriend ('never seen a Ferrari inside a Ferrari before', the town barber will say), stealing the scene from the priest at a Christmas mass where everyone was looking at him and her.

Then there were sparks with his city, the night a billiards competition was being filmed at the Castle and he turned up very late, amidst impatient extras. Prato forgave him, while Francesco began the series of 'silences' that fatally, after that film that softened the world, semantically accompany his parable. The silence after the inspiration and success of the great films came to an end; the silence of him overwhelmed by the demons that consumed him as a man and the physical silence brought about by the accident at home. Until the silence of the last day, mockingly heightened by the great uproar over the death of Silvio Berlusconi, who took everything from the news and emotions. Poor Francesco, who paid the price to the man who was everything in communication: matador and master. He who communicated with a glance. Obviously, in silence.